Deir el-Hagar

Deir el-Hagar, the ‘Monastery of Stone’, is a sandstone temple on the western edge of Dakhla Oasis, about 10km from el-Qasr in the desert to the south of the cultivation. In ancient times it was known as the ‘Place of Coming Home’, or ‘Set-whe’. After being buried in debris and sand for many centuries by the huge dune that can still be seen to the south, the temple has been uncovered, restored and partially reconstructed during the 1990s by the Dakhla Oasis Project with the Supreme Council of Antiquities and is now open to visitors.

The temple of Deir el-Hagar represents one of the most complete Roman monuments in Dakhla Oasis. Olaf Kaper of the Dakhla Oasis Project suggests that this isolated site was a festival temple rather than a cult temple, which are more usually found in the centre of a community. Dedicated mainly to the Theban Triad and to Thoth, construction of the temple began during the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero (AD 54-68), whose cartouche can be seen in the sanctuary. It was built to encourage farmers to settle in the area, along with irrigation works, villages and the mudbrick Roman farmsteads that can still be seen in the area surrounding the temple.

Nero’s successor Vespasian (AD 69-79) added decoration to the sanctuary, Titus (AD 79-81) then added the porch and finally Domitian (AD 81-96) decorated some of the doorways and the monumental gateway. Other Roman rulers have contributed to the decoration, with the latest inscription in the temple dating to the 3rd century AD.

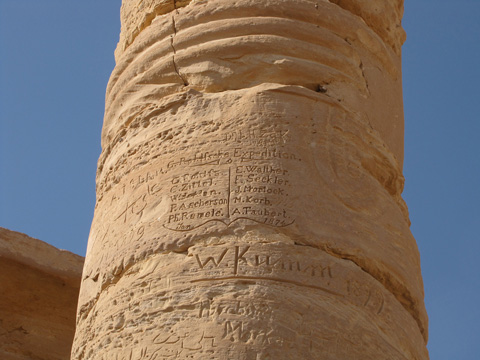

The temple building measures 7.3m by 16.2m and has a well-preserved outer mudbrick enclosure wall where some remains of painted plaster can still be seen. The main gateway is in the eastern side of the enclosure wall, while another gateway to the south, in the temenos wall of the sanctuary, depicts many Greek inscriptions and graffito written by early travellers who wanted to record their visits to this sacred place. During the 19th century, travellers began to visit Deir el-Hagar, many leaving their names incised high on the columns and walls of the porch, an indication of the level of sand fill at that time.

On a column in the columned hall, are the incised names of the ill-fated expedition led by Gerhardt Rohlfs in January 1874. This expedition travelled to the west of Dakhla into the Great Sand Sea but they had not anticipated the size and extent of the huge sand dunes. After three days they had to turn back and take a more northerly route to Siwa. Also in 1874 Remale cleared sand from the sanctuary. In 1908 Winlock published the first extensive description of the temple and during the 1960s, Ahmed Fakhry excavated in front of the porch.

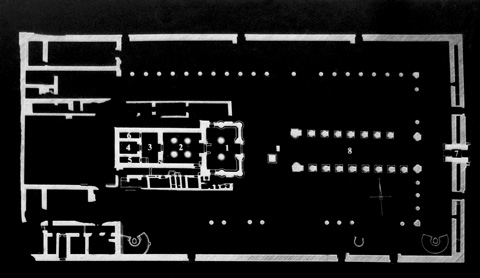

A processional way leading from the main gateway up to the temple entrance still has remains of round mud-brick columns which would have been part of pillared halls flanking the entrance and a few small sphinxes found in this area can now be seen in the Kharga Heritage Museum.

The entrance to the temple is through a screen wall into the wide pronaos or porch, which has two columns. A doorway leads to a small hypostyle hall containing four columns which in turn opens into a hall of offerings before the central sanctuary. The sanctuary is flanked by two side-chambers – to the south is the staircase which would have given access to the roof and to the north a storage chamber.

The sanctuary itself was decorated with a magnificent astronomical ceiling, dating to the rule of Hadrian (AD 117-138), which had painted reliefs including an arching figure of the goddess Nut representing the sky and the god Geb, who symbolises the earth. In the centre of the ceiling the god Osiris is represented by the constellation of Orion, while other astronomical features are represented by various deities whose task was to maintain the universe. Also depicted on the ceiling is a representation in the form of a sphinx, of the god Tutu, whose temple has been excavated at Kellis. The fallen zodiac ceiling from the sanctuary has been re- assembled for viewing outside the temple building. Such a scene is unique in temple sanctuary decoration.

The west wall at the rear of the sanctuary gives prominence to the primary gods of the temple, Amun-Re and Mut. The south wall portrays the Theban Triad of Amun-Re, Mut and Khons, as well as Seth, Nephthys, Re-Horakhty, Osiris and Isis, and Min-Re. The northern wall includes the Theban Triad alongside the Heliopolitan creator gods, Geb, Nut, Shu and Tefnut. Here also is an important representation of the Dakhla god Amun-Nakht (seen at Ain Birbiya) and an inscription from the sanctuary denotes his earliest known visit to the oasis. This desert god, who seems to have characteristics of both Amun-Re and Horus, is shown here with his consort Hathor. Thoth, another deity well-represented in the oases, is seen with his local consort Nehmetaway. These are all deities which occur in paintings in Shrine 1 at Kellis and probably at the temple at Ain Birbiya, showing that they were probably partly of local origin or variation.

Remains of other still partly-buried structures surround the temple and there is a block field to the west of the enclosure. In the immediate vicinity there is much evidence of agriculture in Roman times, including pigeon-houses. To the north-west of the temple is a Roman Period cemetery where crude human-headed terracotta coffins have been uncovered.